On Blackout Poetry and Eclipses

John Panza

On 8 April 2024, my city will experience a total eclipse for a couple exhilarating minutes. In times past, such days were venerated, gods worshipped, and animals and people sacrificed. I get the day off work, and the local professional baseball team – playing their opening game of the 2024 campaign – plays an hour later due to this astronomical rarity. The fear by the team brass isn’t angry baseball gods but snarled traffic being caused by rubberneckers. In a time of pitch clocks, even an occasional ballgame can be delayed.

To celebrate the eclipse, a local literary society hosted a blackout poetry contest. The best blackout poem – with a combination of both the subject and the form reflecting the blackout theme – wins publication and all the accolades that come with having one’s poem published by a local Midwestern American literary society on their website. I’m sure the poems submitted are creative takes on the blackout theme. I’m sure the existent texts they used – from literary works to newspaper articles to recipes – will be delightfully altered. I look forward to reading the winner’s poem.

The question I have, though, is what the poem will look like, typographically and topographically. There are options at play here with concrete poetry, especially if the poem is itself wrought from the subtraction of existing text. I could spend pages and pages on this through academic pedantry, but instead will offer up an example. Consider the following quick “blackouts” of a passage from Wharton’s The Age of Innocence.

First the original passage:

Though there was already talk of the erection, in remote metropolitan distances “above the Forties,” of a new Opera House which should compete in costliness and splendour with those of the great European capitals, the world of fashion was still content to reassemble every winter in the shabby red and gold boxes of the sociable old Academy. Conservatives cherished it for being small and inconvenient, and thus keeping out the “new people” whom New York was beginning to dread and yet be drawn to; and the sentimental clung to it for its historic associations, and the musical for its excellent acoustics, always so problematic a quality in halls built for the hearing of music.

Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

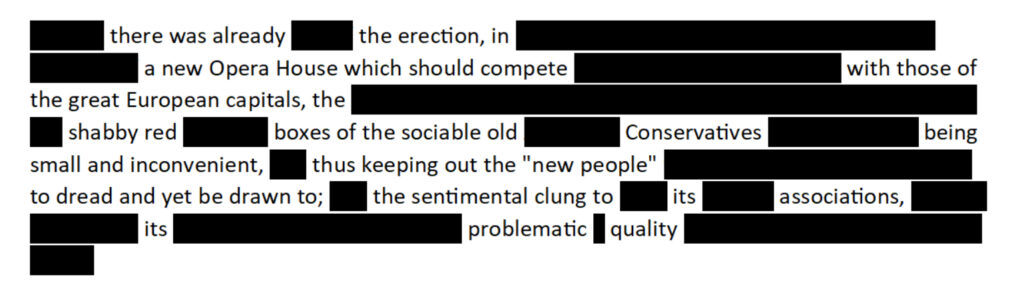

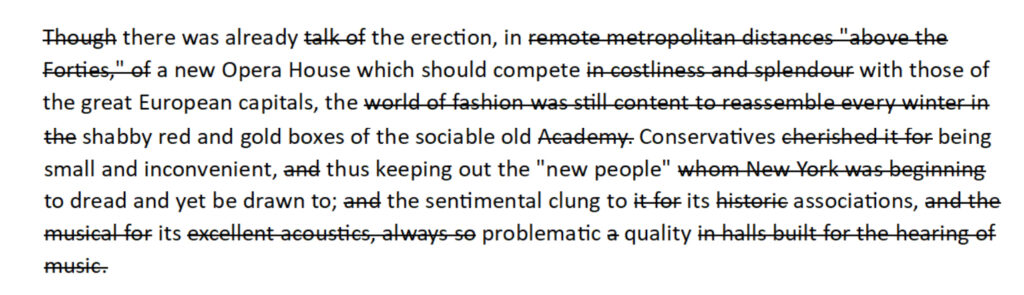

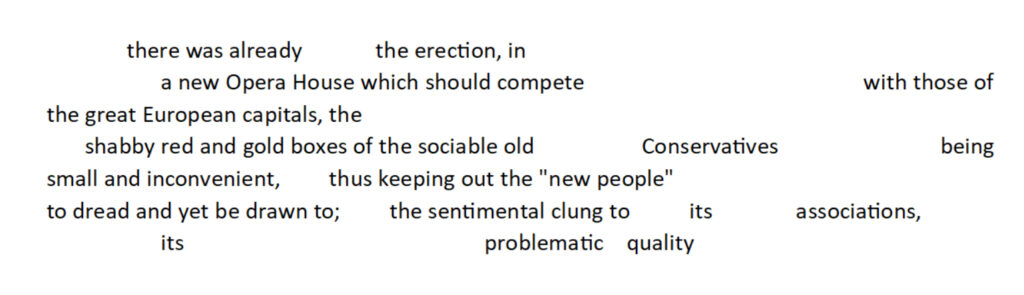

Now here are three takes on the form and content of “blackouts” of Wharton:

My apologies to Wharton, but I’m a working class academic and now I have your attention. Consider the effect of each of the typographical choices made. Knowing the original passage as you do, think about the effects of the three “blackout” techniques: the redacted report, the Editor edits piece, and the Cummingsesque poem. (A fourth would be a complete left justified version that blows the white space away completely.) The topography created by those typographical choices do seem to ask us as writers to consider the audience’s experience with the poem, something I have found concrete poetry doesn’t always do. When subtraction has resulted in addition, what is no longer there can take many forms and inform the reader’s experience with the piece. Seeing it, not seeing, kind of seeing it, etc. matters.

It was Pound who pared down an unwieldy poem about the Paris Metro’s damp denizens into a brief, haunting haiku-ish lyric showing those same folks vanishing into the city’s wetness. The original version of the poem is out there. It’s cumbersome in a way that the final version is not. It’s worth reading in its original, 20+ lines and then, for fun, doing what I’ve done above topographically to it to get to Pound’s final version. Maybe blackout poetry is more than what is left but what is still (essentially) there. An eclipse totality is only a couple minutes, but you still see the sun (kind of).