Interview with Yvonne Battle-Felton

Interview with Yvonne Battle-Felton

Author

Questions by Peter McAllister

When did you know you wanted to be a writer?

I have loved telling stories ever since I was a kid. But I was horrible at it. It took me ages to get through the telling. Usually, I would be laughing so hard that I couldn’t even get the story out. So, in order to have the story properly appreciated, I had to write it down. So, I wanted to be a writer as a kid. It was one of the best feelings. I lost that for a while. I’m so glad I have it back.

We’re huge fans of Remembered, your amazing and heart-wrenching first novel, which was longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction (2019), the Not the Booker (2019), and shortlisted for the Jhalak Prize (2020). What was the process of writing it like?

Thanks so much for the kind words. I loved writing Remembered. It was emotional and rewarding in so many ways. I wrote Remembered for my Creative Writing PhD. So, throughout the writing process I had Jenn Ashworth as my wonderful thesis supervisor. As for writing, I write character driven prose and write out loud. I started writing with a title (it was Letters to Edward at first), a question, and a character. Tempe sort of came to me with a snatch of a phrase and I loved her right away. I didn’t really know her at first. But, I wanted to. I knew what she wanted but I wasn’t sure what she was wiling to do to get it. I wrote scenes with her in different settings with different characters and that made me even more curious about her. I had to keep writing to figure out her story. It broke my heart when I realized she wouldn’t live through the telling of it.

For me, writing the characters in scenes helps me to grow to be curious about them. It also helps me to see who they are when they get what they want, when they’re in love, when they’re in crisis, and when they’re alone. The more I get to know them, the more curious I become about them. Also, since I don’t plot, getting to know the characters is the best way for me to find the story they want to tell.

But, I also write out loud in character. It helps me tap into the rhythms, silences, emotions and voice of the piece. It makes for some interesting looks on the train.

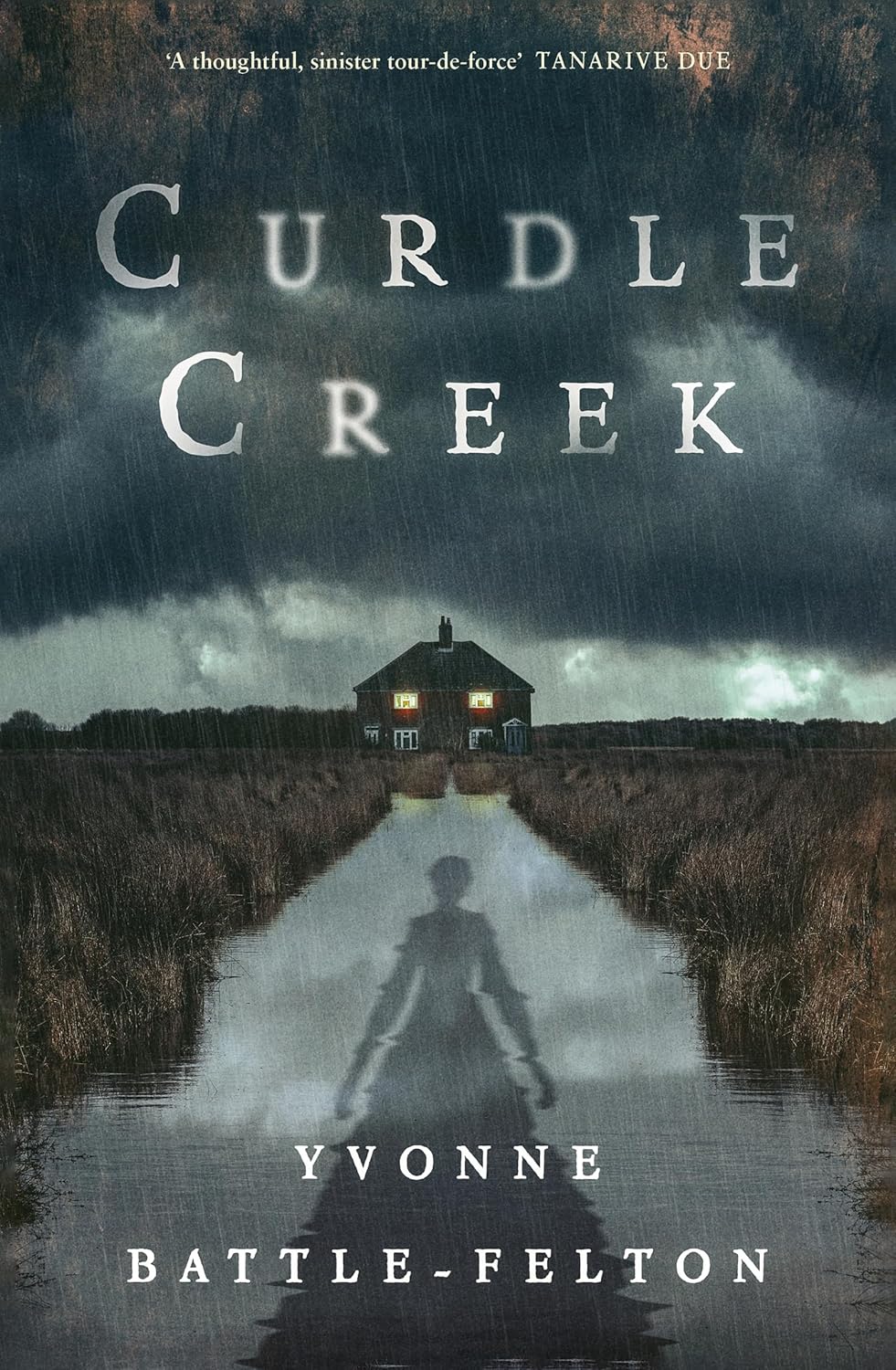

We absolutely loved Curdle Creek, your second novel, which has been described as a “gorgeously written, surrealist folktale that goes bone deep. Compelling, thought-provoking, thrilling, haunting.” Can you tell us a little bit about the research that went into it?

Thank you and what a wonderful quote! Curdle Creek is a fictional town so I could make up the rules, rituals, and ordinances based on what the town needed. Most of the research was in the writing of it. Trying to balance what I “know” about the town with what the writer needs to know was quite the balancing act. I had a word document to keep the rituals straight since they were getting more and more complex. But other aspects of research were woven through the book. I wanted to know what people wore at certain times, when things were invented, what things were called. Even though I really didn’t say when Curdle Creek was and even though they don’t use technology, I wanted the town to have access to some things and not others. I wanted them to choose isolation.

Osira’s experiences in Curdle Creek have some resonances with the experiences of the townspeople in Shirley Jackson’s famous story ‘The Lottery’. Was Jackson’s work an influence on the novel, and what other writers have inspired you?

It absolutely was! I’ve been fascinated with ‘The Lottery’ ever since I read it decades ago. I was curious about what it would take for people to move there, what keeps people there, and what makes people have and raise families there. After I read it, I wondered why people wouldn’t move away. Now, I know it isn’t always that easy to pick up and move. Sometimes, there isn’t anywhere else to go or it seems that way. And other times, it’s what you know. But someone had created a short film adaptation of the story. They introduced a truck in their version. The truck meant that people could leave and had seemingly chosen not to. Or, they had chosen to leave and come back. But the adaptation didn’t have any people of color in it. In the story, ethnicity was not named. That meant the characters could be anyone. Not that you want to necessarily picture yourself in the story but, what if you did? Why could the person who adapted the story imagine people staying by choice (there was no mention of being forced to stay there, there were roads and ways in and out) but not able to imagine people of color? So, I wondered what it would be like if something like ‘The Lottery’ took place in an all-Black town and Curdle Creek was born.

Quite a few writers inspire me! Some are Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston, Tananarive Due, Mary Shelley, Edgar Allen Poe, and Jenn Ashworth. Each inspires me for different reasons at different times.

How did you come up with the ingeniously conceived and ominous rituals that dominate life in Curdle Creek, an all-Black town in rural America?

What a great question! I have no idea. I feel like the characters and the town came up with their rituals. A few years ago, I had a commission to write a flash fiction short story for a crime anthology. It was my first visit to the town of Curdle Creek and I met Osira (whose name was Riley then) and Mae. They were 16 and on the cusp of their first Moving On. They had only heard rumors about the rituals. They were curious. They didn’t have a choice. A year or two later I was invited to revisit the town and write a longer short story. Then, the girls had decided to walk away from it all. Revisiting the town for the novel, I knew they had a population policy and I knew about the Moving On. But, I had changed and the characters did too. Riley was now Osira. She was also older. She had done and seen some things and now knew loss for what it was. The rituals sort of came out from getting to know her and the town and the hold the past had on them. They also came from reading the newspaper and looking at society and thinking: what’s the worst that can happen?

You’ve said that you often write about motherhood, secrets, ghosts, identity, and relationships, as well as about characters underrepresented in history. What draws you to those recurring themes?

I’m sure each of these themes is rooted in questions I’m exploring within myself. I’m a mother and a daughter. I write a lot about those relationships probably as a way of interrogating my own. I’m interested in boundaries and roles and how we navigate who we (and characters) are beyond those roles. I’m also drawn to write about home because I’m not sure where I want that to be. I write to figure things out. I am interested in characters who are underrepresented in history because their stories are important. They have stories we can learn from. I also write to explore characters underrepresented in history to show them as full and complex characters who are the main characters in complex stories.

You also write fantasy and nonfiction for children (with three titles in Penguin Random House’s Ladybird Tales of Superheroes and three titles in their Ladybird Tales of Crowns and Thrones). What are the main differences/similarities you’ve discovered between writing for adults and children?

It was such a treat to re-write myths for children. I think I play more with words when I’m writing for children. Depending on what I’m writing, I also have different kinds of fun. I’m more conscious of how I get to the heart of the story. I also try to remember to be hopeful. When I’m writing nonfiction for adults, I’m honest in different ways than I am when I’m writing for children. When I’m writing fiction for children I try to edit to be sure I’m not writing lessons in to the story and that I’m creating characters who make mistakes, have flaws, feel a variety of emotions, get into trouble, etc…While I don’t set out to write books that invite kids to fall into some of the situations my characters get into (certainly not with the re-writing of myths and also not with the mystery series I’m writing), I’m also not trying to write books that feel like I’m teaching kids how to be kids.

You’re a busy person; as well as writing, you’re the Academic Director of Creative Writing at Cambridge University. You also host your own literary events, podcasts, talks, and workshops. Tell us a little bit about what you’re working on at the minute and what do you love most about interacting with other authors.

Thank you for that and thanks so much for asking this question. I want to create a project, platform, and business that brings people together over books. I want to connect readers with authors. I love hosting literary events and bringing people together. For me, it’s about community and relationships. If I can create a space that’s welcoming where people make friends, meet authors, and fall in love with a book or two, I’m happy. I think I can help authors promote their books and make it easier for readers to explore these books. I host book clubs with readings and DJs, quiet book clubs, the podcast, and literary events. I’d like to add retreats, writer in residencies, and a book club for middle grade readers. I think of it all as developing readers.

I love interacting with authors. I love hearing how they create, research, and explore. When it comes down to it, I’m far more sociable than I think I am or just nosier.

Do you have any advice to give to aspiring and emerging writers?

Write and share your writing with writing groups and readers when you are ready for feedback on it. You’ll get a variety of feedback. Some readers will get exactly what you are trying to do. Others won’t. Your target audience does not have the benefit of being in your head so if people do not see the writing as clearly as you do, it is just a reminder to open the piece up so that they can see (feel, hear, experience, know) the story the way you do. Please do not get defensive. It can be hard to receive feedback on early drafts. It can be even harder to give feedback to someone who does not want to receive it. Write and when you are ready to share it, share it.

About Yvonne Battle-Felton

Yvonne Battle-Felton is Associate Teaching Professor at Cambridge University, where she is the Academic Director of Creative Writing. An American writer living in the UK, her debut novel Remembered was longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction (2019) and shortlisted for the Jhalak Prize (2020). She was commended for children’s writing in the Faber Andlyn BAME (FAB) Prize (2017) and has three titles in Penguin Random House’s Ladybird Tales of Superheroes and three titles in Ladybird Tales of Crowns and Thrones. Yvonne’s second novel, Curdle Creek (Henry Holt/Dialogue Books), a gothic horror inspired by Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery’, has been nominated for The Shirley Jackson Award (Novel).