Interview with Tim Hannigan

Interview with Tim Hannigan

Travel writer

Questions by Kate Horsley

We love the way The Granite Kingdom weaves together in-depth research into geography, history, art, landscape and travel literature with on-foot research and a warm and entertaining vein of personal reflection! How did the idea for it develop and what were your favourite – and least favourite! – parts of the research process?

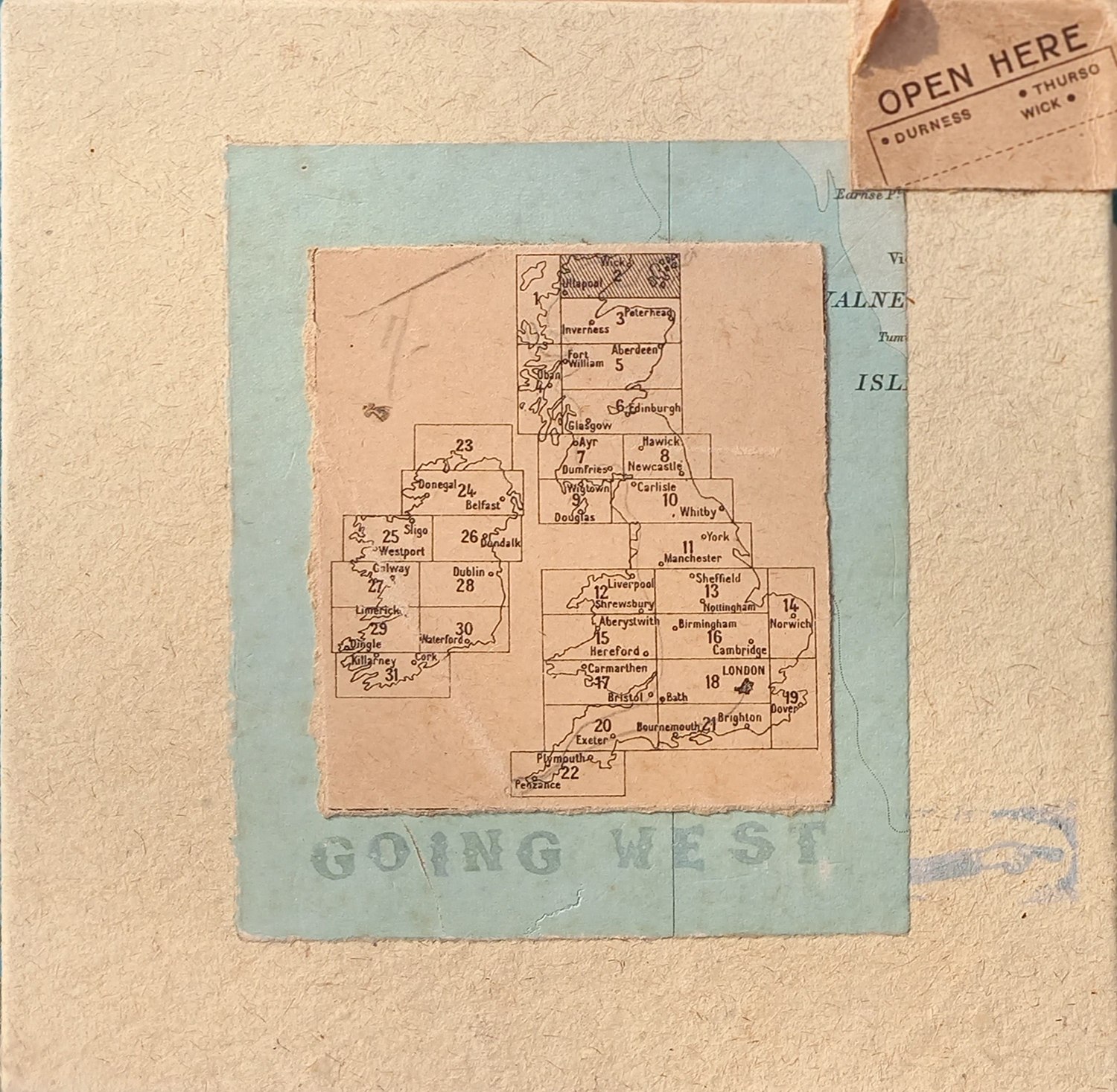

Thank you! I’m glad that you appreciated that wild mix of components! The idea to write something about Cornwall, addressing themes of history and culture, had been around in the back of my head for years. For a while I considered writing a more straightforward narrative history, perhaps with each section hinged around a particular place within Cornwall.

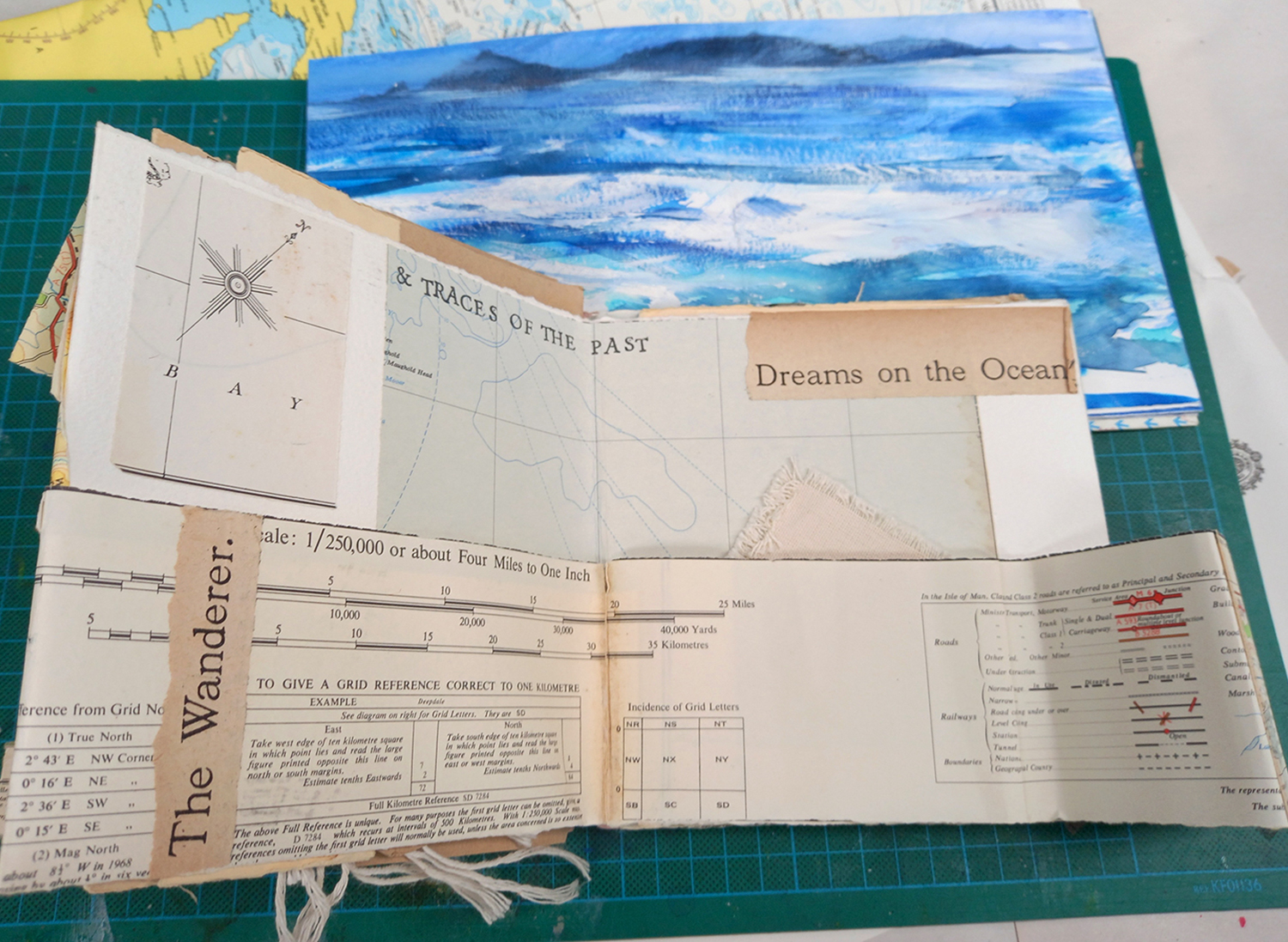

But that wouldn’t have given me the flexibility to jump backwards and forwards in time, to make indirect links between topics, or to bring in the reflective personal elements. In the end, I realised that making it a travel book would give me the perfect structural foundation. That’s the great attraction of travel writing: it provides a solid organising principle for all sorts of disparate elements.

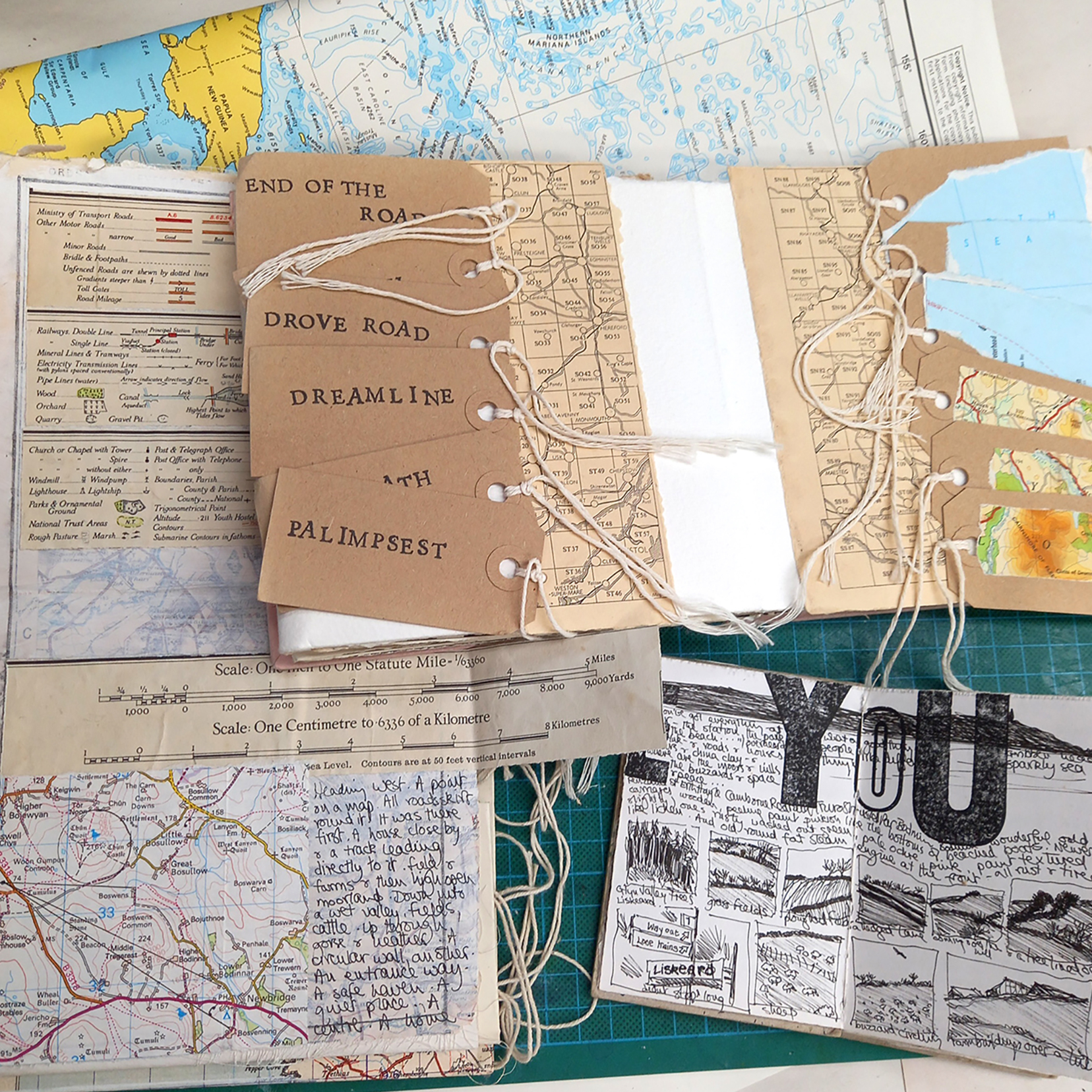

The most exciting moments involved stumbling across an individual story from the past, and then chasing down the details – the transatlantic voyage of the Cornish farmer James Hoskin, for example. I also loved the journey itself – a 300-mile walk from one end of Cornwall to the other. But there were definitely times, slogging along with blistered feet at the end of a long hot day, when I wasn’t enjoying myself!

You’re from Penzance in Cornwall, a place which is so rich in history, legend, and myth. When you were growing up, did you have a favourite mythic story, traditional tale, or local legend?

I was particularly fascinated by Carn Kenidjack – a granite outcrop on the moors near St Just. There are various creepy stories about it collected by 19th-century folklorists. I wasn’t properly familiar with those as a child; but the place definitely still had a vaguely sinister reputation, and the devil and the headless horseman were rumoured to be at large in the vicinity. We spent a lot of time wandering around near Kenidjack as kids, and it was a great place to give yourself the heebie-jeebies on a foggy day.

Really, though, the stories that most caught my imagination weren’t from folklore; they were the stories my dad told me from his time working as a deep-sea fisherman, especially the ones involving sharks, conger eels and killer whales – monsters just as thrilling as giants and spriggans and piskies.

Your career has varied from your time as a professional chef to studying journalism to teaching English, tour guiding, and now writing and academia. Did you always dream of doing what you do now, or does it feel like the unexpected culmination of a series of adventures?

In a way the answer is yes to both! I wanted to be a writer, from a very young age, and somehow always assumed that I eventually would be. But I had no real idea how to go about it. Throughout my late teens and early twenties, while I was working as a chef, I wrote story after story, tried to write novel after novel. But I never really made any serious attempt to do anything with them; most went straight into a bottom drawer. I didn’t even know that “creative writing” was a thing you could study. Looking back, I think that was a very healthy approach: I was learning my craft without the distraction of pursuing publication. It was when I was working as an English teacher in Indonesia in my mid-twenties that I started publishing things – newspaper and magazine features, mostly travel-themed. And then, within a few years, writing had become my main occupation.

The one thing that I definitely wouldn’t have foreseen at the outset was my academic career. I had no interest in going to university at eighteen, and I was quite hostile to formal education in general. But now I’d say that I’m doing my dream job, analysing texts and teaching writing and literature.

Along with all the books you’ve published, you write short fiction, including your brilliant story, ‘On the Border’, anthologised in Cornish Short Stories: A Collection of Contemporary Cornish Writing. How does your approach to writing a short story differ to that when writing non-fiction? How does it feel to move between more and less factual forms?

For a long time, I had a conviction that a story – or a poem – should always be about something: people in a scenario that speaks to a theme, even if that theme is never directly mentioned. I think there was a bit of a Hemingway influence going on there. I wrote lots of pieces like that when I was younger, and my short stories came from a very different place to my nonfiction. But these days I’m much more inclined to blur the line between “essay” and “short story”, to play around on the border between fiction and nonfiction. Sometimes these are ideas that arise in my nonfiction book projects, but that are more readily explored in shorter forms.

In your writing, external journeys of travel are intricately interwoven with internal journeys of thought, empathy and discovery. Do you find that physical journeys unlock particular forms of writerly discovery?

Absolutely. As I said, the physical journey provides the narrative core of the book. But it’s much more than a structural device. During any journey, you encounter the unexpected: incidents, accidents, detours, places that were nothing like you expected, conversations – the unplanned. When you set out on a journey as a writer, you have to accept a certain lack of control: you are going to write about what happens along the way, but you don’t know what’s going to happen! The other important thing about a journey – especially a journey on foot – is that you spend a lot of time inside your own head, distilling vague ideas, picking at problems, working things out, and that’s a very important part of the writing process.

You write about Cornwall with such compelling curiosity, insight, humour, and affection. At one point, you ask, “do we need the gazing outsiders to tell us that our place is special?”, an observation that evokes an intrinsic tension between travel-writing-about and belonging-to a place. What observations do you have about writing about a somewhere you’re discovering vs. somewhere you’re from?

Tim Hannigan reading from The Granite Kingdom at St Just Library, photo by Peter McAllister.

It’s much, much easier to write about somewhere you’re not from. Writing about travel is, inevitably, also writing about the self. But place and self are far more clearly separated when you write about somewhere that’s foreign to you. When you write about where you’re from, the dynamic is far less stable. Everything is ambiguous – including the identity of your readership. Are you writing first and foremost for others from the same place, or for outsiders? And there’s also a danger – especially if you’re from a place like Cornwall – of slipping into a kind of chippy nativism, of writing against outsiders. I’m not sure if I got it right, but I did my best to embrace the anxiety and uncertainty of the process, to make it a part of the story.

As well as being an author, you’re an academic who teaches creative writing at universities. What do you love most about teaching creative writing, and how do your writing and teaching processes influence each other?

I teach both creative writing and literature, which is the best of both worlds as far as I’m concerned. The formal study of creative writing, for me, is about understanding and articulating the writing process – being able to say what you did in a piece of writing, and why you did it and how you did it. Engaging with that – whether as a student or a teacher – makes you a more controlled and methodical writer. But it’s actually the literary studies, rather than writing practice, that I most enjoy teaching. Engaging with critical theory and working on close analyses of books that have little to do with my own creative practice makes me a more attentive reader – and being a reader comes before being a writer.

What are you reading at the moment and what are you writing at the moment?

I’ve been teaching a module on literary modernism for the first time this semester, which has been a great excuse to reengage with a whole lot of authors – Virginia Woolf and James Joyce and Katherine Mansfield and others – that I haven’t read for many years. I’m also reading a lot about Irish history, and especially the history of the way land in Irish has been controlled and contested. This is for my current writing project – which will be another book blending travel writing with history and all sorts of other things. It’s at a very early stage, but there will be another long journey on foot later this year.

Finally, what advice could you offer to writers who have recently started out?

Read, read, read – and read widely. Don’t restrict your reading to your own preferred genres; read everything and anything you can get your hands on.

About Tim Hannigan

Tim Hannigan was born in Penzance in Cornwall in the far west of the United Kingdom. After leaving school he trained as a chef and worked in Cornish restaurants for several years, before studying journalism at the University of Gloucestershire. He also worked as an English teacher and a tour guide before becoming a full-time writer. He is the author of several narrative history books including Murder in the Hindu Kush (The History Press, 2011), which was shortlisted for the Boardman Tasker Prize; Raffles and the British Invasion of Java (Monsoon Books, 2012) which won the 2013 John Brooks Award; and A Brief History of Indonesia (Tuttle, 2015). He also edited and expanded A Brief History of Bali (Tuttle, 2016) and wrote A Geek in Indonesia (Tuttle, 2018). His most recent book is The Granite Kingdom (Head of Zeus, 2023). He also co-wrote Jokowi and the New Indonesia (Tuttle, 2022), the authorised biography of Indonesian president, Joko Widodo, with Darmawan Prasodjo. Visit Tim’s website or find him on Twitter.