Interview with Graham Mort

poet and short fiction writer

Questions by Peter McAllister

Tell us a little about the place you live and space you write in. What can you see from your window when you work?

I live in a village on the Lancashire/ Cumbrian/ Yorkshire borders. I have an office in upstairs room with an old 1940’s mahogany desk and an Apple Mac computer. From the window, I can see our garden with its greenhouse and tall rowan tree. The garden slopes down towards a small valley with a stream, a ruined barn and hawthorn hedgerows that have run wild. Sheep graze in the fields beyond the garden and a herd of belted Galloway cattle come right up the fence. Ash trees with the first signs of die-back beyond, then fields rising to a distant view of Ingleborough. The mountain looks different every day, often starting off with a pennant of cloud, often invisible through mist and rain, spectacular under snow that turns pink when the sunset reaches it. The sun and moon rise above that eastward line of moorland, shining through the branches of the rowan tree in the morning and early evening.

What is your writing routine and what do you draw inspiration from day to day?

I’m at my desk by nine am in winter, earlier in summer. I work for a few hours each morning, but try to get out to walk or cycle in the afternoons. Climate change has made that difficult recently with constant rain and wind, so that’s become a pressing theme or undercurrent in some of my work. I suppose my writing nearly always proceeds from actions or things in what we think of as the ‘real’ world, though I’m not so sure about that supposed reality. All writing proceeds from memory because the present moment is evanescent, then lost. And memories are changed by the mind’s invention. Then the future’s out there like untrodden snow. Sometimes things I’m reading percolate and rise to the surface, triggering the start of something. Sometimes dreams that return and won’t go away. Travel has always been a big stimulus. I also alternate between poetry and fiction and they’re very different disciplines.

Nature and landscape play a huge role in your work: moments of awareness connecting people to the animal world raise questions about the human condition, our relationships with the environment and with each other. Where do you find the natural details for your poems and stories?

Even looking through a window, things constantly change, as many people realised during lockdown. I guess writing is the art of noticing things, of giving attention to the world. Sometimes things observed/experienced take on an aura of significance and you know you’re in a moment that will lead to a new piece of writing. Then there is the irreducible quality of ‘things’ as well as the sense of actions or events in the world. Letting the senses in is very important, rather than closing them out. I don’t accept the distinction between the natural and human worlds since we are ourselves a species in that ever-changing context. I don’t really accept the distinction between inner and outer worlds either, since our inner worlds and perceptions of the outer world constantly modify each other. I’m interested in machines as well as organic things and see them as an extension of our human nature and creativity. Human beings are constantly learning to be alive; writers and other artists especially so. I’ve been reading the poems of the 8th century Chinese poet Du Fu recently and what strikes me is the extraordinary detail in the writing allied to a deeply meditative state of being.

As well as being an author, you’re an accomplished musician and photographer. Do you feel that photography and music are parallel processes to your writing? How do these artforms inform your writing process?

Photography has been a constant practice at home and whenever I’ve travelled. I use a conventional camera, rarely a smartphone. It’s not necessarily the finished photographs that help me to recall experiences (though I do store and review them), but the act of selecting and focusing on a particular subject, editing as I swing the viewfinder. I think that intensifies any experience. Then there is what you don’t or can’t photograph – extreme poverty for instance, which I’ve seen in Africa – which is intensified by those deliberate omissions, through ethical editing. Writing and photography are reclusive activities, depending on a sense of isolation to some extent. I’m not very sociable, I guess! Music is a different thing for me, a communal activity, a cooperative ideal. I’ve played in bands, and that’s been to do with creating a social space where a group tries to work together, balancing discipline with individual expression within ensemble playing. Often frustrating, because that requires technical ability and a kind of ESP – it’s a different kind of experience that focuses on anticipation as the music unfolds. That’s never been directly linked to my writing, but I’m sure there are subliminal connections and listening to music and musicians has been very important to me.

We are very excited that you’re contributing a flash fiction piece to Inkfish! What defines flash versus longer short fiction? Does planning and writing a flash piece feel very different to writing a short story? And is flash fiction a completely separate form to prose poetry, or are they too similar to keep fully distinct?

I don’t get too hung up on distinctions between forms. All writing is a continuum with considerable linkage and spillage between them. I have a tendency to write short stories that are a bit longer than literary magazines like these days (around 6,000 words.) That makes room for characters and locations and patterning through recurrent or resonating images. I got interested in ‘flash’ or micro-fiction through teaching the form. I think very short fiction can seem a little glib at times, though I’ve also read some terrifically compressed pieces that are emotionally moving. I like to write micro-fictions up to about 1,500 words, trying to find what can be achieved in a short space through omissions as well as inclusion. There’s still space for humour (or irony) in that. I’m still experimenting and finding my way, really. I’m still never sure whether a new piece of writing will develop into a poem, a longer story, or a very short one. I guess that decision is taken early on in the process because I rarely convert one to the other.

There are some amazing moments of intensity and epiphany in your stories – for example at the end of award-winning short story, ‘The Prince’. Is emotional intensity as important as characterisation in crafting a successful story and are both more crucial than plot?

Very little happens in the present moment of my stories, most of the events can be attributed to reflection, refraction, memory, the actions of consciousness. Especially consciousness interacting with the putative present moment, which gives most of my stories and poems their texture. Wolfgang Iser, the literary critic, recognised the play between anticipation, retrospection and that evanescent present moment in literature and in life. So, I guess I privilege the inner life of my characters and narrators over their actions. Though there has to be interaction with present moment dimensions of reality, otherwise the work would be abstract. Above all, my characters are haunted by memory and responsibility through their actions. They’re certainly not taking part in action-packed thrillers. I suppose I believe in celebrating the complexity of ordinariness, the richness of the everyday, the contradictions within characters who one might think unworthy of note if we met them outside a story. So, I’m interested in the way actions, decisions, omissions, memory and speculation form the tissue of our consciousness and the texture of a narrative.

Your short story collections - Touch, Terroir , and Like Fado - foster delicate resonances between individual pieces, landscapes and experiences. How did you decide which pieces to include in them and how did you know the best way to order those pieces?

I think that process has been different in each case. Touch was written over a very long period of time, Terroir over several years, and Like Fado over quite a compressed period of time. It might depend on where I am when I’m putting the stories together – a lot of work in Like Fado was done when I was working in Cape Town, living alone with time to focus intensively. I’m not sure I put that much time into ordering the stories, but try to make the shift from one to the other satisfying in some way, whether that might be subject matter, or narrative method such as voice or point of view. I know a lot of the significant connections can be subliminal rather than consciously arrived at.

Is the process of crafting a poetry collection similar to the process of collecting together stories?

Yes, it can be, though poetry is always running in parallel to other forms of writing. You can experiment with very short forms in all sorts of ways, from the form itself to the sense of voice and the angle of attack. Again, assembling a collection is about addressing a range of theme and form. Sometimes I use the spellchecker to identify my own writerly ‘ticks’ and eliminate them, so even diction become a distinguishing feature of variety and an important aspect of form. I’ve written a number of long poems and sequences, too, and that is a similar process of considering the white space between poems, as well as those moments of typographical density where the reader becomes involved with morphemes, phonemes, symbols, metaphors; the meanings that arise from active language, rather than the silences or interstices that live between them.

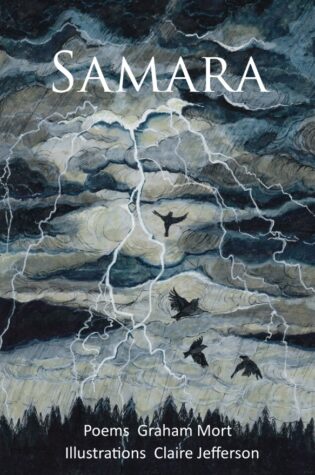

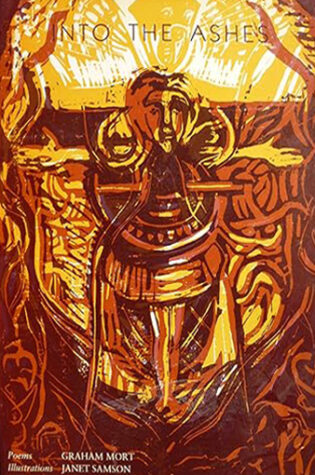

You recently collaborated on an illustrated poetry collection - Samara - with artist Claire Jefferson. What was it like to put a book together in a collaborative way like this? Have other books of yours drawn in visual art in a similar way?

Yes, for two early books, A Halifax Cider Jar and Into the Ashes, I worked with visual artists, though in slightly different ways. It’s good for me to surrender control and work with the imagination of another artist in a different medium. I really like the sense that images and poems can create a new thing that is not illustrative, but combinative. And I like having to understand another approach that will be integrated into my own.

You’re a lifelong teacher and mentor to other writers. What do you love about teaching and do you have any favourite stories drawn from your teaching work?

I trained as a teacher after working in a psychiatric hospital and I’ve worked at all levels of education from very young kids to PhD students: some of that in schools, some of that as a freelance tutor, and quite a few years in academia. I’ve specialised in distance learning, which works exceptionally well for creative writing. But I love the drama and tension of face-to-face teaching. Stories? Well, I like it when students answer back. When I started my university job, an exasperated American student interrupted me to say, ‘OK, Graham, we’re talking now.’ That was a salutary lesson and a very funny moment – and we’re still in touch. Stevie’s back in the USA now and sent me his book about moles recently. He commissioned a poem from me for that, knowing it would be a subject close to my heart.

What are you working on at the moment?

A new book of poems and two books of (longer and shorter) fiction. They were all started in lockdown when covid hit. The microfiction seemed to come from nowhere and I was writing two or three stories a week for a period. That’s calmed down a bit now. I like to get a first draft and let it lie for a while, then start re-drafting, which I think of as the real work. So, all those books are approaching completion.

What advice can you give to writers just starting out?

Well, you need to read of course. Become a good reader and read between the lines. Though the connection between reading and writing can be over-stated. It’s never been absolutely obvious to me. They’re very different practices, but we are the first readers of our own work and reading is essential to the process of revision that I spoke about above. So read to appreciate technique. Don’t just read in the medium you want to write in, read everything. Text has invaded our lives, especially in urban settings, so it’s become a part of our daily perception of the world. I read all sorts of stuff, from stories, novels and poetry to current affairs, cultural history, sociology and technical manuals. Read the hand-book for your motorcycle or cafetière or dishwasher. They have their own sense of ethics and morality, their own tone and pitch for our attention. All that gets drawn into stories in particular, but they’re brilliant for ‘found’ poems, too. And persist. Accept the criticism you secretly know is true, but stick to your guns as well. Be a little stubborn but stop short of blind vanity. Of course, that’s not as easy as I’ve just made it sound!

About Graham Mort

Graham Mort is emeritus Professor of Creative Writing at Lancaster University, and a prolific writer and poet. He has worked internationally in many countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle-East. In poetry, Graham has won a major Eric Gregory Award for his first book of poems as well as prizes in the Arvon and Cheltenham poetry competitions. His latest collection, Black Shiver Moss was published by Seren in 2017. ‘The Prince’ won the Bridport short fiction prize in 2005 and his short story collection, Touch, won the Edge Hill Prize in 2010. A further collection of short stories, Terroir, appeared in 2015 and a new collection, Like Fado and Other Stories, was published by Salt in 2020. Visit Graham’s website. Find Graham on Twitter.