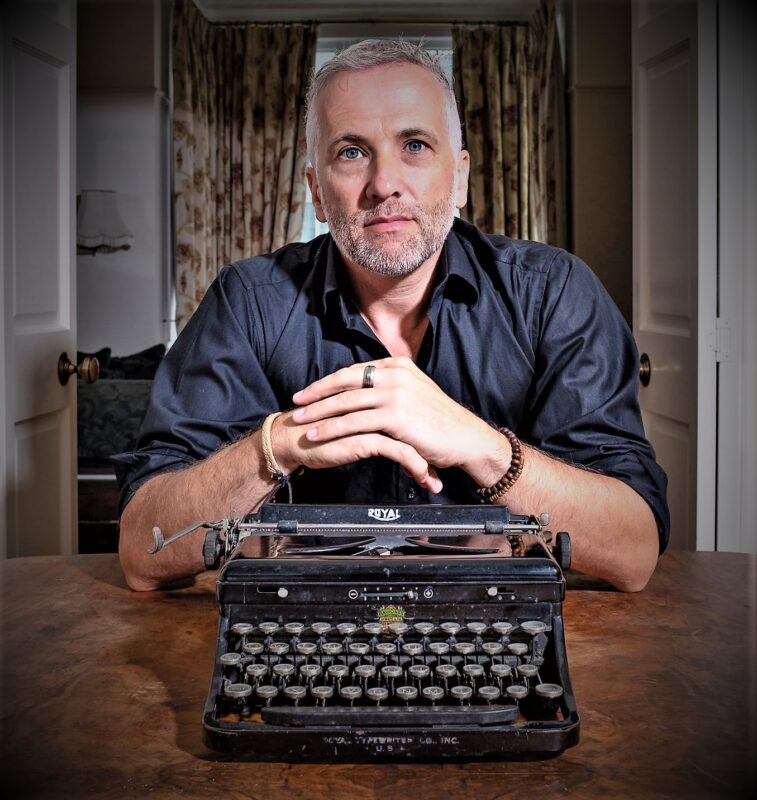

Interview with Tom Vowler

novelist and short fiction writer

Questions by Kate Horsley

Tell us a little about where you live.

A small bohemian town in Devon that’s twinned with Vires (France), Salfit (in the West Bank) and Narnia. It shuns chains, Tories and once had its own currency.

Are there local stories, myths, legends that inspire you?

The land here is riddled with folklore, Dartmoor in particular, where I’ve set a novel and a couple of short stories. So many of its spaces feel liminal, portals to ancient events and times, which you can hear on the breeze if you listen hard enough.

Earlier this year, your story ‘Voyagers’ won the V.S. Pritchett Short Story Prize. In it, the moors with their “pale grasses” and kestrels form the backdrop for a brilliantly written, heartfelt tale of female astrophysicists tripping on magic mushrooms. How does the landscape around you infuse your writing?

Those were other moors, but all my work tends to braid story with landscape, the two inseparable for me. We’re not mere inhabitants of the land, but products of it, shaped by its vagaries and textures. That story is of course about a journey, temporal and emotional, one that invites speculation of deep ecology, time and psychedelics.

You’re a passionate advocate for the short story. What feels different – more compelling – about writing short rather than long?

I think I tend to root for the underdog. But also it’s clear to me that some human truths can only be explored in this form, owing in part to the obliquity of its approach, the ineffable subtext permeating the surface narrative. A good story is always about something other than it seems; it defies classification. To borrow from Ben Okri, aside from the sonnet, it’s the most demanding literary form.

We are very excited that you’re contributing some beautiful flash fiction pieces to Inkfish! What defines flash versus longer short fiction? Does planning and writing a flash piece feel very different to writing a short story?

Short fiction’s attendant qualities (ellipses, irresolution, obliquity, precision) are even more heightened in flash. Someone once likened the novel to a marriage, the short story to an affair. Perhaps flashes are one-night stands. Initially, I have little idea what a piece will become, but it lets me know soon enough. There’s a brutality in revising a flash, stripping it down to the bone, and beyond. I feel there’s this greater connectivity with the reader, the contract insisting they do much of the work.

You’ve emphasized the importance of the “felt” over the “known” in short stories, saying “I want to feel flayed, my mind or heart colonised for twenty minutes or so.” How do stories flay us? Why do good ones leave us with “more questions than answers”?

I said that?! You should never trust a writer in interviews. I suppose I want a shift to occur in me that, as with a poem, I’m not entirely certain why or how it’s achieved its goal. The best stories undo us, change small parts of us, so we’re not quite the same after reading them. We’ve witnessed their brilliance and have forever become disciples to the form. I recently read of the short story that a good one is like spending time with a friend’s cat, stroking and befriending it, only to get home and realise it’s scratched you. Stories should scratch us.

Short stories, flash, prose poems, novellas-in-flash feel like such current forms, like works in progress. What risks might writers take to push the envelope and what do you see short stories evolving towards?

Nobody – editors, agents, readers – wants to read the same tired old stories again and again…and if they do, it’s the writer’s duty to challenge this, remove their comfort blanket. I’ve such admiration for those who play with form, embrace hybridity, take the creative path less trodden.

Something you said that I especially loved was to “mine your biggest fears” when writing. If inhabiting a fictional psyche is akin to acting, what’s your method for transmogrifying your own fears into a character’s?

If we’re to truly explore and present resonant characters, we are obliged to look inwards, inhabit uncomfortable territory. Perhaps this is the closest writing gets to therapy. How can we understand our characters’ fears if we have no insight to our own? To write is to be vulnerable, open to all that may rise from the primordial swamp of our emotional, psychological lives. Like moths, we must flutter close to the flame. I’m deeply mistrusting of veneers.

Staying with fears for a moment, your novels, That Dark Remembered Day and What Lies Within, are compelling literary thrillers that explore “the darkest corners of the human heart”. How much do you find yourself gazing into the abyss as you write? Does it gaze into you?

I think that phrase is more a marketing gimmick than anything, a cover blurb. I’m interested only in storytelling; this is my one duty – to the narrative. To my best ability to construct a story that in some way leaves the reader not entirely the same person they were at the start. I’m not much interested in entertaining, and perhaps in this regard I’m drawn to the more crepuscular shades of human endeavour. Observing the genocidal behaviour of many of our leaders, it would be disingenuous and neglectful of me to occupy overly palatable, bathetic ground.

What’s the most dangerous, weird, or just plain “out there” anecdote you could share with us about your research process?

Obviously I can’t share that one! I did once ask a friend to punch me in the face as hard as he could, so I could capture it in words. He really took to the task.

When you gather stories for a collection, how do you select and order them?

I guess I try to manipulate readers’ emotions, who likely take their revenge by not reading them in chronological order.

What are you working on?

A memoir and being a better person.

About Tom Vowler

Tom Vowler lives in the UK, where he writes and edits fiction. His collection of short stories, THE METHOD, won the inaugural Scott Prize and the Edge Hill Readers’ Prize. His debut novel, WHAT LIES WITHIN, is a psychological suspense set on Dartmoor, and his second, THAT DARK REMEMBERED DAY, is meditation on fatherhood, war and the natural world. Tom is an associate lecturer at Plymouth University, where he completed his PhD. DAZZLING THE GODS, his second collection of stories, was published in 2018, and his latest novel, EVERY SEVENTH WAVE, is out now. More at www.tomvowler.co.uk