My Head For A Tree by Martin Goodman

Book Review by Kate Horsley

In the scorching expanse of Rajasthan’s Thar Desert, where temperatures soar to 50°C and dust-laden winds howl at 150 kilometers per hour, lives a community that would die for a tree. Literally.

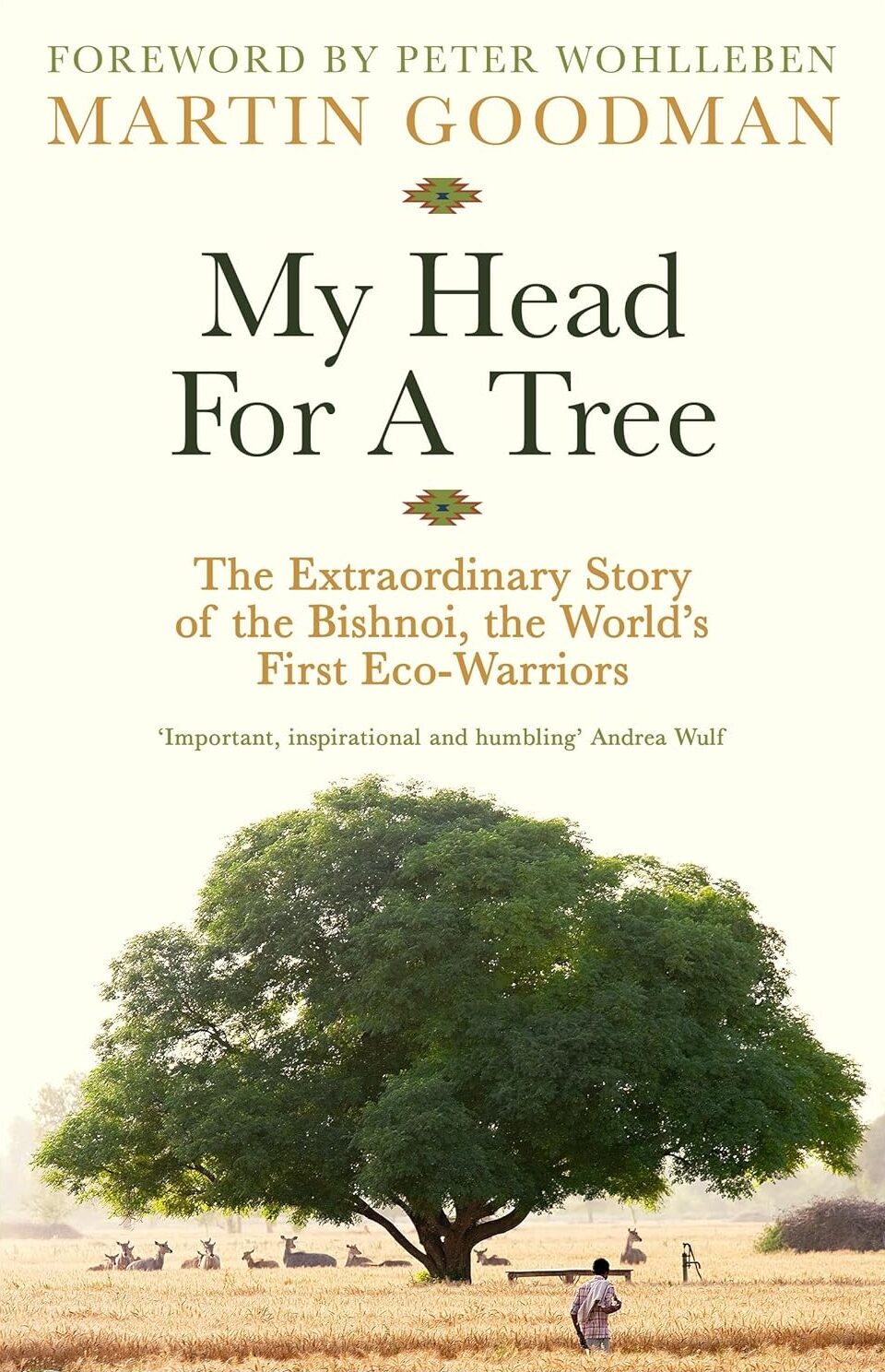

Martin Goodman’s My Head for a Tree: The Extraordinary Story of the Bishnoi, the World’s First Eco-Warriors introduces us to the Bishnoi, a 600-year-old community whose members have made the ultimate sacrifice not for country, not for king, but for khejri trees and blackbuck deer. This isn’t environmental activism as we know it—this is something far more profound.

The book opens with a scene that seems almost mythical: In 1730, a woman named Amrita Devi pressed her body against a tree trunk as axes swung toward it. Her final words, before her head was severed, would echo through centuries:

“Sar santey rukh rahe to bhi sasto jan” — “My head for a tree; it’s a cheap price to pay.”

By day’s end, 363 Bishnoi villagers lay dead, each having chosen execution over witnessing the destruction of their sacred groves.

What makes Goodman’s account so compelling is that this isn’t ancient history. When he asks a modern Bishnoi child if he would sacrifice his life to save a tree, the boy’s response is immediate: “Trees are for all. I am for just one family.”

Goodman writes with the eye of an anthropologist and the heart of a poet. His prose captures the paradoxes of desert life, where “peacocks fly up to treetops from where they shriek at each other” while “black humped bullocks bellow like hippos” in the monsoon rain. But beneath this lyrical surface runs a deeper current of urgency about our planetary crisis.

The Bishnoi (literally “Twenty-Niners,” after their 29 religious commandments) aren’t passive tree-huggers. They’re fierce protectors who have taken on Bollywood superstars, government officials, and armed poachers. The book introduces us to Ram Niwas, who at fifteen joined the “Bishnoi Tiger Force,” going unarmed against armed men to protect wildlife. We meet Pushpa, whose husband died fighting poachers and who now raises orphaned gazelles in her home, nursing them with the same tenderness she would show her own children.

Perhaps most remarkably, we encounter Radheshyam, who single-handedly forced the government to install reflectors on power lines to prevent the Great Indian Bustard—a critically endangered species—from electrocution. When officials ignored his pleas, he climbed the pylons himself.

These aren’t isolated acts of heroism but expressions of a worldview so alien to modern sensibilities that it’s almost incomprehensible. For the Bishnoi, environmental protection isn’t a cause to champion—it’s the very foundation of existence. They don’t need to be convinced that climate change is real or that biodiversity matters. They’ve structured their entire society around these truths for six centuries.

Goodman wisely avoids turning this into either a noble savage narrative or a simple call to action. The Bishnoi face real challenges: poverty, drought, and the encroachment of modernity. Their way of life is under constant threat. Yet they persist, guided by principles that seem almost extraterrestrial in our current moment.

The book’s power lies not in its environmental messaging—though that’s certainly present—but in its portrait of people who have solved the fundamental problem of human relationship with nature. They’ve internalized what environmentalists struggle to articulate: that we are not separate from the natural world but part of it, and that its destruction is literally suicidal.

Brian Eno’s endorsement calls the book “sensitive and engaging,” hoping “everybody reads it.” That hope feels both urgent and necessary. In an age when environmental catastrophe looms and activism often feels performative, the Bishnoi offer something rare: a proven model of sustainable living backed by unwavering commitment.

My Head for a Tree is ultimately about love—not the sentimental kind, but the fierce, protective love that parents feel for children, the kind that doesn’t count costs or calculate odds. The Bishnoi have simply extended that love beyond the human family to encompass all life. In our current moment, such love might be the only thing that can save us.

This is essential reading for anyone grappling with climate despair or wondering what genuine environmental commitment looks like. Goodman has given us more than a book—he’s offered a mirror, reflecting back our own relationship with the living world and asking the uncomfortable question: What would you die for?

Award-winning author Martin Goodman has written ten books, both fiction and nonfiction, and a theme common to much of his fiction is the exploration of war guilt. He is Emeritus Professor at the University of Hull (where he was formerly Professor of Creative Writing) and also a publisher at Barbican Press.