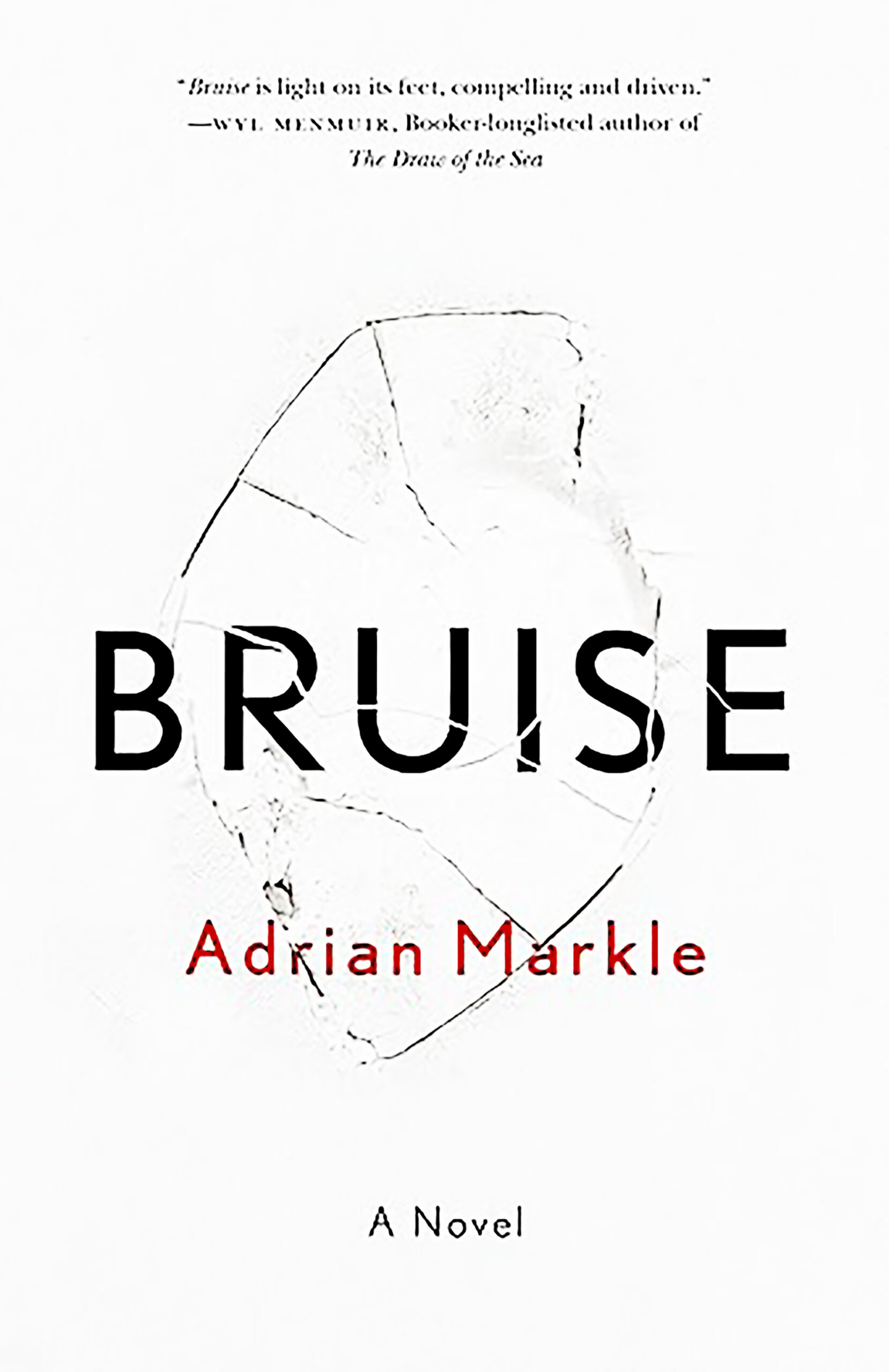

by Adrian Markle

Review by Lee Horsley

Adrian Markle’s Bruise (Brindle & Glass, 2024) tells the extremely compelling, often heart-wrenching story of Jamie Stuart, a badly injured martial arts fighter who has had the dedication to succeed internationally, becoming a middleweight champion of the world. The novel centres on Jamie’s post-injury return to the fishing village he grew up in, to a bleak sea that overwhelms him with “its vastness, its dark emptiness…the relentless sound of it.” Throughout the novel Markle powerfully evokes the sense of a once thriving place that now embodies only loss and despair:

“It seemed the only thing they’d hauled out of the water here lately had been his father’s body some months before, his flesh grey and yellow and wrapped in thin-blooded bruises, with lungs full of seawater and enough booze in his veins to kill a better man.”

We come to understand why the son didn’t return for his father’s funeral, the reasons all too apparent in the family life that has made Jamie into his adult self. Bruise is both a coming of age and a return to home novel: the relationship between child and man is developed through interlocking time lines, Jamie’s homecoming alternating with chapters set in his boyhood. As readers, we’re given a cumulative sense of the ways in which childhood patterns of behaviour, injuries and losses have, by his early 30s, made it near impossible to escape.

Having spent his whole life fighting to survive, Jamie compulsively returns to memories of the early conflicts that haunt his life: the remorseless brutality of his father, the death of a younger brother in part because Jamie was himself unable to show fear and back down. His oldest fears grew from being taken to fight on the beach – “watching his father mark a wrestling ring in beach sand with his toe, and what inevitably happened when Jamie lost.” It was an experience that gave him the grit and toughness that sustained him in his professional fights. At the same time, it ensured that, underneath even his most triumphant moments, there was a chasm of fear.

From the time Jamie returns home, he veers between hoping he might be able to help others while at the same time feeling that “There wasn’t anything for him here, he knew now. No job at the hospital, no job at the bar, not even coaching kids in their stupid karate.” As his despair deepens, his brother works to persuade him that the only chances left in town are at the seedy margins of low-level crime, and he comes perilously close to feeling that his brother’s life of small scale drug dealing may be his only path to survival.

Bruise is a very impressive first novel, and Markle is right to avoid a resolution dominated by the dangers and high tensions of a crime narrative. It may instead be that Jamie has to reconcile himself to living without decisive moments of defeat or glory, accepting smaller steps towards rebuilding a life that might ultimately be redemptive. In a key scene, he teaches two young boys the most rudimentary skills of fighting along with the kind of resolution that has driven him in everything he’s accomplished: “you can get down on purpose or I can put you down, but either way you got to get used to fighting your way up from the dirt.” Five out of five stars on this brilliant debut from us: highly recommended!