In the twilight of my twenties I boarded a Southwest 737 to San Diego. That trip, I wasn’t just trying to solve a military conspiracy, but rekindle a relationship, recover inner truths I’d lost, secrets I’d buried so deep they might never come out. It was probably too ambitious for Labor Day Weekend.

Toward the end of my flight, a woman in the middle seat to my aisle turned to me and said, “You and my son-in-law have the same look.”

“Thanks.” I was wearing Danner boots, designer jeans, a floral shirt. I was a bit unshaven given the early nature of the flight. It was a weird thing to say, what this woman had just said.

“It’s a good look,” the woman said. She had Greek evil eye charm earrings. “What do you do?”

“I work at a podcast.” In fact, I was an assistant producer for the nationally-syndicated podcast Detective Radio, based in Denver, Colorado: we investigated the weird in the world, the strange tales which illuminated some random aspect of life with greater clarity. The premise sounded vague, but our founder had won a Genius grant and we had the funding.

Her eyes lit up. “What is the podcast about?”

“Weird stuff,” I said. It was always awkward to explain; after all, I didn’t typically host the podcast; usually, I was the one who set up all the interviews.

“How interesting.” She held out a tin of Altoids. “Want a mint? I don’t know if you have a hot girlfriend waiting for you at baggage claim.”

Another strange thing to say. I took the mint. I was not about to contradict her on that account, that I was headed to San Diego on business, primarily; though I had seen several women over the years, no relationship had stuck.

It was not in this vein that I’d texted Veronica late the previous night, though I suspected she, too, remained single; that there were some nights in college, walking home from parties, when we’d bid each other goodnight outside our respective dormitories for awkward lengths of time, just one false move between exchanging one form of relationship for another. In those moments, circumstances tugged us back from the precipice—we were both seeing other people, then—and so we’d turn away from each other, the nervous chemistry evaporating the further we were apart, distance providing the antidote to our desire. At least, that’s how I remembered it. I was a bit of a romantic then, so my interpretation could have been totally off-base.

Another fact about Veronica: she was an oceanographer at Scripps, studied algal blooms, red tides, omens of death, but with the cheeriest personality one could summon in the face of such topics. Perhaps this was what drew me to her in the first place.

“What weird stuff is going on in San Diego?” the woman asked me, an Altoid clacking in her mouth.

“We’re doing an episode on this navy operation named Argus. It involved the atmospheric testing of hydrogen bombs in the South Atlantic.”

“So naturally you need to go to Southern California.”

“They did all the planning for it in San Diego.”

“When was that?”

“The 50s.”

She leaned back in her seat. I thought we were done, but then she spoke again. “Argus.” She tested out the name in her mouth. “Wasn’t that the guy who got turned into a peacock?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Argus. He was in the Greek myths.”

“I honestly haven’t really looked into it yet.” I pulled out my notebook. “Tell me more.”

“Argus was a giant,” the woman said. “He had many eyes, all over his body.” She gestured at her torso. “Now Zeus, I think he had fallen for a woman named Io. He turned her into a cow, I think it was, to trick his wife, Hera. But she knew—” She wagged her finger. “Hera knew Zeus was cheating on her, so she appointed all-seeing Argus to guard Io and prevent Zeus from visiting her.”

“What happened?”

She frowned. “I think Zeus had Argus murdered.”

“Ah, okay.” I could hear the slats of the plane as they adjusted for our descent.

“In death, Hera removed his eyes and placed them on a peacock. So that’s why peacocks have eyes. What, is that not weird enough for you?”

“It’s weird all right.” That marked the end of our conversation. I was tired and eager to get going.

When the plane landed and I deactivated airplane mode ahead of the cockpit’s announcement, I saw that Veronica had responded.

Cool, she wrote. How about dinner?

Sure, I replied.

The beating of three ellipses in my messaging app. For a moment, I could ignore all the people prematurely retrieving their bags from the overhead bins. But in the black glass of my phone, I saw a dark-suited man stand in the aisle. He seemed to be staring at me, but he was wearing Aviators, so it was hard to tell. When I turned to him, he looked away, as if I’d caught him doing something wrong.

#

That afternoon, jet-lagged and reluctant to do any real work before my dinner with Veronica, I drove my rental Subaru to the Salk Institute and parked in a dubiously legal spot. I walked onto the campus and into the courtyard. The interlocking offices faced each other along the dazzling concrete plaza, the small fountain trickling toward the Pacific, looming immense—the whole complex perched on a cliff like a Greek temple. I was all kinds of tired but this place was special. It made my heart sing for the first time in a long while.

Then a guard asked if it was my car parked in the yellow zone. I said yes, I was sorry, I was lost, and the guard persuaded me to reunite with my Subaru.

My father, a medical researcher, used to work at Salk, and when I was a kid he’d take me around, leave me to sit in the stark geometries of the courtyard, only occasionally helping me apply sunscreen to my face, my eventual pink-and-blistering skin inevitably aggravating my mother. All that was a long time ago; my father had been dead for several years now. Heart failure. The medical definition of death was that a person’s heart stopped, but when a person died of just that, it seemed a little disappointing. Nothing else? I thought my father was strong enough to battle multiple ailments, but instead it was the singular one which claimed him too soon. Life was strange like that; in a blinding flash, one reality could give way to another without any agency on my part. However, on occasion, if I didn’t push for something, that particular occurrence might never happen, even if, in that smallest moment, it seemed as expected as gravity.

My mother lived in Colorado now, to be closer to me. I thought I should bring her something, thought about doubling back for the Salk gift shop, but then I realized the gesture might make her more sad than any other feeling. So I left, checked into my La Jolla hotel, hiked my computer to a café overlooking the shore, and over a nitro cold brew I sketched out the questions I had planned for the admiral when I interviewed him on Monday. When I grew tired of work, I thought about Veronica; we hadn’t seen each other in years. How many? Six? Then I checked my watch. It was time.

#

We met at a restaurant on the water, a surf-and-turf place where all the wait staff wore Hawaiian shirts and modern, Polynesian-styled art was hammered into the walls. It was one of those places on Yelp that listed three dollar signs on the menu and enough glowing reviews to convince a prospective diner it was worth it.

When I entered, she was already at a table. She was looking at her phone, her hand pushing back her dark hair; she looked stressed. Then she saw me and all that stress seemed to evaporate.

“The radio legend returns.” She gave me a hug.

“Sure,” I said. In seeing her, I felt a spark of something at one point I hoped I forgot, but I was glad I hadn’t. “Have you found Atlantis yet?”

She laughed. “Not yet, Mark. That one I still haven’t pinned down.” She shook her head.

“Surely you’ve been looking, though.”

“I have,” Veronica said. “So I have.” She put her hand, awkwardly, on the table. “Shall we eat?”

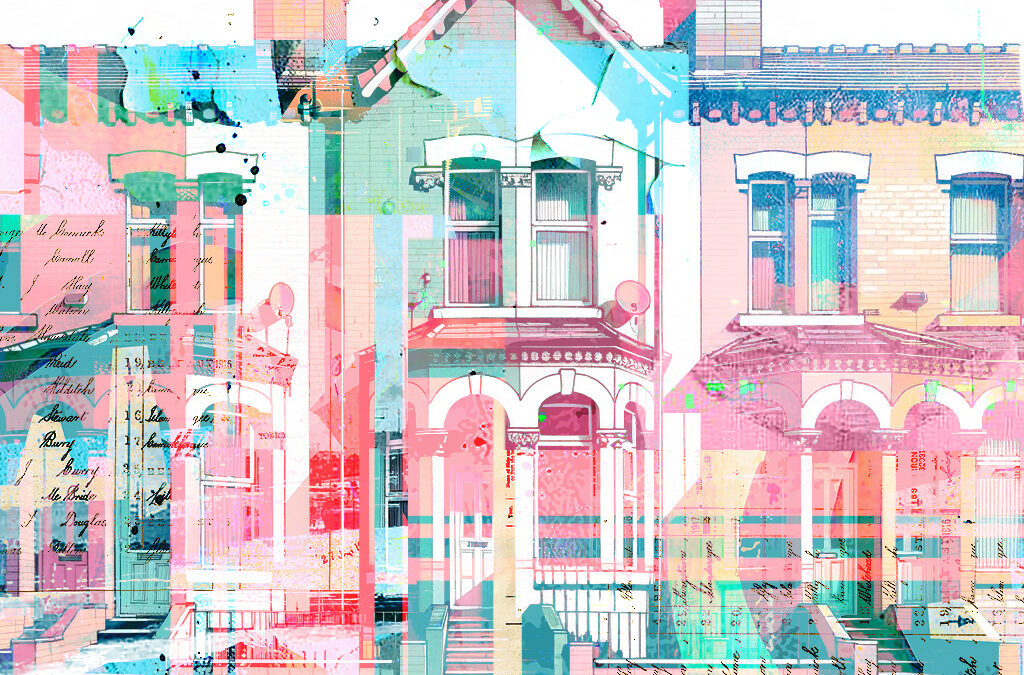

I had a glass of Pinot Noir but she said she couldn’t drink that night. For a while we talked about small subjects; the weather, baseball. She asked about my mother; I told her she was doing well. Once we were in the midst of our meal—I had ordered king crab, she had ordered linguini—I couldn’t help but notice, on the wall behind Veronica, a painting. It looked like a green and blue fan with dazzling cerulean blue circles behind it, a stylized depiction of a bird’s body, its head and beak and the fleshy bits beneath it.

“What are you looking at?”

I pointed.

“Oh, you mean the peacock?”

“Is that what it is?”

“Yeah, sure,” she said. “Those birds are really mean. They’re pretty, and confident, I guess, so people like to keep them around as pets, but they’re bullies, really. There are a lot of peacocks which run loose in San Diego, I think.”

I remembered seeing a bird like that as a kid. “It’s strange,” I said. “A woman on the flight was telling me about peacocks.”

“A woman,” Veronica said suggestively. “Tell me about her.”

I cackled. “Well I guess she was flirty. She was a grandmother, maybe. I told her about this story I’m doing on Operation Argus.”

“Oh, right, you mentioned this over text,” Veronica said. “I think there’s someone on staff who might be able to help you—Naomi. Her husband used to work at Los Alamos.”

“Oh, cool.”

She checked her watch. “Oh, shoot. Is it bad if I head out?”

“What’s the rush?” I asked, not disguising my disappointment well.

“Well…” she laughed. “I need to go to bed early. There’s this work-office athletic event tomorrow afternoon, like a barbeque. You could come, if you wanted. You wouldn’t have to swim.”

“What sort of swim?”

“It’s around the Scripps pier. It’s a tradition. Then we hang out.”

“I’d love to swim,” I said, though of course I hadn’t gone swimming in years.

“Have you been swimming?” Veronica asked, before backpedaling. “I’m not saying that you don’t look fit—it’s just a difficult swim, even for swimmers.”

“Nah, I’m down.”

She nodded reluctantly. “All right. Come to the pier at two p.m.”

After we paid, I kissed her on the cheek goodbye; I lingered at the table as she disappeared through the door.

Then I asked the waiter about the painting.

“It’s a print of a famous painting by a local artist,” the waiter said. “Solomon Fresno.”

I parsed the name. “Do you know where I can find him?”

“He died a few years ago,” the waiter said. “Cancer, I heard. There’s a small retrospective up at Balboa Park, I think.”

“Thanks.”

I bit my lip. On Monday I was supposed to talk with Admiral Veidt about Operation Argus. And I knew from some background research on Veidt that his wife’s maiden name was Fresno. It was becoming distinctly possible that Operation Argus had something to do with peacocks after all.

#

In my hotel room I turned on the television and found the Dodger game. My father was born in Los Angeles and therefore loved the Dodgers. I watched them when they were good, but he watched them all the time, even when they sucked. My mom never really liked baseball all that much, and most summer nights she would knit in silence while my dad lived with every televised ball and strike. But after my father died, she suddenly took on an interest in the game. One afternoon, after she’d moved to Colorado, she asked if I wanted to go with her to Coors Field—the Dodgers were visiting the Rockies. So we went, and sitting in those vertiginous seats of the upper deck, we watched the little blue-and-gray men dart onto the field to face the purple home team.

As soon as we got to our seats, Mom ordered us two Coors Lites from a concessions guy lugging a crate of the stuff. My mom drinks wine, if at all, so this was unusual. Moments later, she stood and cheered when Cody Bellinger hit a line-drive triple, the ball ricocheting off the right field corner, bouncing out of Charlie Blackmon’s glove.

I turned to her in astonishment. “What’s gotten into you, Mom?”

She shrugged. “We’re winning.”

A few innings later, she told me something I had never heard.

“Your father proposed to me at Dodger Stadium, you know.”

“He did?”

“He did. At the parking lot behind home plate, you know where it overlooks the city? It was beautiful that night. Of course I said yes.”

I was surprised they had never told me. Was baseball the binding glue I had never seen between my parents?

“So seeing the team, it reminded me of your dad.” She turned to me. “When are you going to settle down?”

I laughed.

Knowing she had struck a nerve, she struck it again just as hard. “You can’t be a bachelor forever. You work too hard sometimes.”

I took a sip of the Coors; it tasted like shit.

“I’m trying.”

“Well, you have to try a little harder.”

Max Muncy hit a double and knocked Justin Turner home.

“Like Mr. Muncy!”

That night, after I drove her home, I headed toward my apartment, but as soon as I saw my complex in the windshield, I decided to keep driving, head deeper into the plains. I didn’t know where I was going, but eventually I stopped at a 7-Eleven. Not sure what to do when inside, I bought a Coke Slurpee. My father used to buy them for me when I was a kid. The drink was sweet and bitter, and it made me cough. I drove home with it in the cup holder, but didn’t drink much of it. At home I poured it in the sink. Rinsed the cup. Then I threw it in the recycling.

In that hotel room, as I watched Joc Pederson strike out, I still wasn’t sure why I had bought that drink that night. Of course I knew why, but I didn’t want to spell it out.

#

The next morning, since I had a few hours before the swim, I drove to Balboa Park, a glorious hodge-podge of Spanish Revival architecture which had been built for a couple of world’s fairs in the early twentieth century. Within this complex was an art museum which had been designed to look like a 400-year-old Argentine cathedral. Opening the glass door, I stepped inside the air-conditioned building, showed my press credentials to the front desk. They directed me to an exhibit across the hall.

I read the opening panel, which explained Solomon Fresno was an artist who served in the Navy in the 1950s, and that many of his early works revolved around marine life. After he left the Navy, however, his art became more abstract, revolving around the form of the eye. I stepped further into the exhibit. Sure enough, there was a stuffed peacock in the center of the black room, studio lighting illuminating its shimmering, colorful feathers, its plumage unfolded and frozen in the form of a fan, patterns resembling eyes scattered about its tail. Behind the peacock was a painting like the one I had seen at the restaurant. I moved on, and walked past photographs of atomic tests in the Pacific, the black-and-white horrors of the fleet of ships anchored in the Bikini Atoll, the before-and-after photographs of the bomb going off, the blinding flash, the mushroom cloud, the ships subsequently overturned, videos of the soldiers on skiffs who investigated the wreckage.

Then I saw something else. It was a painting, Andy Warhol-style, of an Erebus-brand spray paint bottle. Tactfully, spray paint was used in the background of the painting to create the image of neon-blue eyes lurking behind the can. A docent was standing off to the side. I pointed out the spray bottle artwork. “What’s that one supposed to mean?”

“Toward the end of his life, Mr. Fresno became interested in modern advertisements, and he painted one hundred and two paintings of spray bottles just like this one,” the docent said coolly, in a voice like a whisper.

“Okay.” I crossed my arms. “Why the spray paint?”

“Some have theorized that he started painting these canisters after the Ozone hole was discovered.”

“Ah, CFCs.”

“That’s a possibility.”

A year before I had researched an episode on CFCs. In the 1990s, chlorofluorocarbons, the chemical intrinsic to refrigerants and aerosols, had been blamed for the deterioration of the Ozone layer. It was a grand success story of environmentalism, this moment when world governments came together to ban CFCs for the greater good.

“What’s the deal with the eyes?” I asked.

She shrugged. “The eyes are a motif throughout his work.” I gave her my card and explained we might want to formally interview her later. She blushed as she walked away. I checked my phone. I needed to get to the beach.

I walked back to the parking lot. The lot was mostly empty except for a black Lincoln idling near my car. It had suspiciously-new California plates, and the windows were tinted, so I couldn’t see inside. For a second I thought that the dark-suited man from the plane was sitting in the driver’s seat, but I couldn’t be sure. I got into my car and tried to forget about it.

#

The pier of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography jutted out from the La Jolla shores like a challenge to the vastness of the ocean. Before arriving, I had looked up the length; it was three-hundred-thirty meters long, almost an entire lap around a running track. Up close, its pillars were barnacled and crusty with entropy’s prejudice against human hubris.

Veronica greeted me at the foot of the pier, where two dozen of the most athletic scientists I had ever seen had gathered around a tent. A few were playing beach volleyball. Others were laying out coolers, picnic tables, setting up a few grills, figuring out how to open packages of tofurkey dogs. A long, steep ramp led up the hill, to the Institution’s main campus, its assortment of buildings perched somewhat precariously on the sand dunes.

“Hey there,” Veronica said. She was wearing a sporty, one-piece racing suit and held a snorkel mask. Meanwhile I was wearing floral trunks and a neon tank top I bought in a surf shop from my hotel, so I guessed I looked out of depth, literally.

“Take a long look,” Veronica said, gesturing at the visible line which had been drawn in the sand, apparently the starting line. “We’re going where many oceanographers have gone before, but no podcasters, probably.”

“Where is that?”

“Around.” She laughed. “You’ve been around the block once or twice, haven’t you?”

This was the Veronica I missed. Funny, sharp-witted. She hadn’t changed at all.

“Who’s this?” a voice came from behind.

“Steve, this is Mark,” Veronica said to a shirtless man with a dollop of sunscreen on his nose. “Steve, you better be careful around him, or news of this event will reach Spotify listeners everywhere.”

Steve and I shook hands; his grip was strong. Then he picked up a megaphone lying in the sand. “See you out on the water.”

“That your boss?” I asked.

“Colleague. C’mon, we’ve got to stretch.”

I leaned forward on one knee to extend my glutes as Veronica went into pyramid pose.

“How was your morning?” she asked. “Any clues?”

“I went to the art museum.”

“Oh,” she said, as if disappointed I hadn’t invited her.

“It was for work,” I said. “What have you been working on, lately? I forgot to ask last night.”

“Well, a red tide knocked out a whole ecosystem near Ketchikan, so we’re working on data from that event.”

“Bummer.”

“That’s probably not as exciting to you as some atomic scandal, but . . .”

“It’s more important,” I said.

She looked at me suspiciously. “In any case, I’m glad you could join us.”

“So am I,” I said. But whitecaps were cresting in the distance, and I was starting to feel nervous.

Veronica and I joined a group of thirty people gathered around Steve and a woman wearing square glasses. “When I blow the whistle,” Steve was saying, “you will all dive in and swim from the right side of the pier, around and back into shore. Naomi and I—” He pointed at the woman with square glasses; I realized this was the woman Veronica had mentioned earlier. “We’ll shadow you in a raft if you run into trouble.” He put his hands on the rim of a trash can in front of him, filled to the brim with ice and beer. “See this? First person back gets first pick of the spoils.” He stuck his hand in the ice and withdrew a bottle of craft beer. “There’s some expensive drank in here, surrounded by Heineken. Swim fast to get the good stuff.”

“Pressure’s on,” I said to Veronica.

“Now you’re talking,” she said.

“I haven’t been swimming that much.”

Veronica looked at me with concern.

“All right,” Steve said. “Let’s get started.”

The blue-gray water crashed and radiated on the shore. I had used to race a lot—track mostly—and over the years I’d gotten used to being less nervous at the start of things, but this time my heart was pounding.

“On the count of three, I’ll blow the whistle,” Steve said. “One. . .”

Veronica was wearing her snorkel mask, now. I really wished I had goggles.

“Two. . .”

I was tense. Even if I hoped to casually compete in a race, I usually ended up competing anyway.

Steve blew the whistle.

I sprinted into the water with all the others, dimly aware of Veronica alongside me. The cold rushed up to meet me. It was tough going to get past the crashing surf, and once I did, the freezing brine surrounded me, the salt inevitably stinging my eyes. Still, I could feel my arms slicing through the water, legs kicking up froth. The water was murky, so it was difficult to see ahead, and every few moments another wave approached and I had to dive under it. I kept up with Veronica, barely.

Soon we had cleared the onslaught of breaking waves, where it was easier to breathe, and we started to settle into a more relaxed place. I could see Steve and Naomi’s dinghy floating just beyond, monitoring the situation. Through the water, Veronica and I shared a smile, though I might have imagined it.

Then I felt an awful pinching ignite in my left leg. The pain spread, inexorably, through my whole body. My kick became lopsided. The pain sharpened, and gritting my teeth, I reduced my stroke to a limping crawl.

My mind flashed to the image of the soldiers investigating the Bikini Atoll wreckage. What it must be like to drown. What Solomon Fresno might have seen, and when. A dark-suited man taking me away.

“You all right?” Veronica asked, treading water beside me.

“Cramp,” I said. “You go ahead.”

She looked at me warily.

“Everything okay?” Steve shouted from his raft, Naomi rowing behind him.

“No,” Veronica said.

“I can do it,” I said, but I was feeling colder by the minute; the pain was intense.

“I don’t think you can,” Veronica said. “Help him up.”

The raft alongside me, Steve reached out with his hand, and reluctantly, I took it and clambered onto the raft. Naomi threw me a towel. I was shivering.

“See you on the other side,” Veronica said, diving back into the water, bubbles in her wake as she joined the pod of swimmers, most of them now turning around the pier, heading back for the beach. Now, a couple had even reached the shore and darted onto the sand—which looked so warm, honestly—and they raced to the bucket of beverages, twisting off a cap of that glorious craft beer.

“Where’d you say you lived?” Steve asked.

“Denver.”

“Not a lot of ocean in Denver.”

“No.”

“Leave him be,” Naomi said, her attention trained on the other stragglers.

“Okay,” Steve said.

#

When I stepped onto the sun-kissed shore, Veronica had already dried off, and she handed me a Heineken.

“Thanks,” I said.

“All the good beer was gone.”

“I figured.”

I limped over to the grill with Veronica. She took a tofurkey dog, but I claimed one of those Walmart hamburgers, the kind that barely registers as meat and has the density and flavor of a hockey puck.

We found a spot in the shade, at the flattened lip of the steep Scripps driveway, overlooking the sand and pier, forever fighting the sun.

“That was fun,” I said. “Except for the part where I almost drowned.”

“You didn’t almost drown.”

“Well, you seemed to think I would.”

Veronica stiffened. “Not everything has to be a race, Mark. What do you have left to prove?”

I took a bite of the hamburger. It was awful.

“Why are you really here? In San Diego, I mean?”

“I told you. Operation Argus. I’m interviewing the admiral tomorrow.”

“I’m happy to see you,” she said wistfully.

“So am I.”

She seemed like she was struggling to put something into words. Finally, she said, “If this is the moment you were hoping to say, what really happened to us, how did we drift apart, I don’t want to take part in your reenactment of The Sun Also Rises.”

There was a sinking my stomach, and it wasn’t just the burger. All I could muster was, “Ouch.”

“I think we could have been something in college, but that was a while ago. We lead different lives, different places.”

“This is the moment you tell me you’re seeing someone,” I said.

“In fact, I’m not. I just think, you know. . .”

“I understand.” I said it like I meant it.

“I’m glad. And it was so good to see you.”

I finished the hamburger. “I’m gonna get another drink.”

#

At the beer bucket was the woman from the dinghy. Naomi. I didn’t really want to talk to Veronica anymore and I didn’t really want to stop drinking, so I fell into talking with Naomi. She studied desalinization. She asked me what I did and I told her. “For a while I lived and worked with my husband in Los Alamos,” she said, her voice low. “It was there, at a bar with my husband’s friends—he’s a nuclear physicist, by the way—that I first heard about Argus.”

“Oh really,” I said, well into my second beer.

“Yes, but this was different. You are of course familiar with the Ozone hole over Antarctica.”

“Yeah. It’s from the CFCs, chlorofluorocarbons.” I blinked when I realized the connection. “The spray bottles.”

“That’s what I thought, too.”

I felt a bout of vertigo. “What do you mean?”

“When the Navy, as part of Argus, detonated three warheads into the upper atmosphere, they also damaged the Ozone layer,” Naomi said. “Think about it. Why do you think CFCs were banned? So the public wouldn’t know the Ozone hole was created by the military nuking the sky.”

“Uh huh,” I said. It was crazy. The tests had happened, sure, but CFCs couldn’t be a hoax. The nefarious chemical the world had united against? How could that be a lie? But I knew the artwork I had seen, and knew it couldn’t be a coincidence, not really. Solomon Fresno had some role in Argus, and he was trying to tell me something from beyond the radioactive grave.

Naomi said she had to talk to Steve, and then I was alone again, standing at the shore of the water, letting the surf come in and return, the massaging sensation of the water rushing back and eroding the sand beneath my feet, sinking me deeper until I had reached a stasis. I texted Veronica, told her I’d call her later. Then I walked back to my hotel, ascended the La Jolla cliff.

#

The next morning I had some time before I talked to the admiral, so I drove to my parents’ old house in Del Mar. It was a small tiny house on the rise of a sandy hill, surrounded on all sides by lurching McMansions. There was no parking available near it, so I pulled further down the street, where I saw another old house, a pink Victorian with wrought-iron gates which I had remembered walking by in my childhood. Then it hit me.

Back then, the owners had kept a large bird in their backyard. My parents had always talked about it, and I thought, going on walks with them, they had pointed it out once or twice. I peered through the gate. I saw a candy-colored gazebo and some elaborate gardening. That was all.

I walked down the street to my parents’ old house. The exterior had seen better days, and the front lawn was a mess of tangled weeds. My father and I used to play catch on that lawn. He had a joy in it I could never understand—when I threw him a baseball, he would catch it quite daintily with his glove. My father had had a lot of disappointments in his life, but he relished simple pleasures. Against all odds, he and my mother had found each other, a partnership of mutual support I had seen little of in my college friends who were now pairing off. I’d been to wedding after wedding, and every time I sat there listening to the toasts, I wondered how long this coupling or another would last, whether it would be cut short by divorce or death or some other terrible word.

The windows were dark, and I wasn’t sure if anyone was home. But I figured I’d knock, see who was around.

A man my age answered the door. “We don’t need any fertilizer.”

“Hi,” I said, handing him my card. “I’m Mark, I work at a podcast. I grew up in this house. I was in the area and thought I’d say hello.”

“Oh,” the man said. “Why don’t you step inside.”

I assented.

“It’s a little messy,” he said. “But you can see we’re trying to fix the place up. I’m Kevin, by the way.” A woman emerged from the living room. “This is my wife, Brenda.”

The smell of the wooden halls brought me back to childhood. There was the staircase where I’d bumped my head as a kid, the odd light through the bay window in the kitchen. The furniture was all different, but these new owners hadn’t yet repainted the walls.

“Brenda, this is Mark,” Kevin said. “He grew up here.”

Brenda shook my hand. “We loved the house. We thought it would be perfect for raising a family. Plus, the schools. You must have gone to some good schools.”

“I guess.”

A toddler wandered into the foyer. Brenda picked him up.

“It’s really funny,” Kevin said, scratching his head. “We seriously thought about naming him Mark, but we ended up choosing Declan.”

“How strange,” I said, trying to smile. “I hope you’re all happy here.”

A few minutes later, I showed myself out and returned to my car. I froze when I saw it.

Standing next to my car was a brilliant blue bird with needle-like spikes coming from its forehead, its green plumage all folded. Then it cawed three times, and shaking its tail provocatively, the plumage unfolded like a fan. The eyes were everywhere on its tail, composed of a dull orange surrounded by an ethereal fluorescent green, and a brilliant, unknowable blue. The tail formed a wall of watchers, evil eyes like in the paintings of Solomon Fresno. Then the bird, suddenly disinterested, walked away and folded up its plumage.

The peacock was done flirting with me. It had made its point and moved on. I had a dark feeling in my heart. I knew what I had in common with this transient, flamboyant bird.

In a daze, I swung by In-N-Out and devoured a cheeseburger at a plastic table alongside the ocean-sized parking lot. The drive-in line was long, and just as soon as a car would leave, another car would enter the line, so that the attendant would march to each succeeding car and take orders from a menu that hadn’t changed much since 1948. It was becoming clearer to me that cycles kept going no matter if I was a part of them or not.

#

I met the admiral at the Hotel del Coronado, an opulent Victorian palace on an island accessible from a bridge which lunged above the city harbor. The hotel’s red Queen Anne dome and white-wooden walls evoked a period of American confidence that had long passed me by.

Despite his age, Admiral Veidt was a starchy, thick man of even temperament. He dined on his cobb salad with gusto as I took small bites of a quiche. I was explaining to him what we were looking for in our podcast, and he had already answered some background questions pretty succinctly.

“It’s fine,” Veidt said. “As I’ve said, I’m happy to discuss any declassified materials.” He put down his fork. “Why are you really here? We could have done this over the phone, though of course I like taking people to the Del.”

I decided it was time to press him. Maybe I could find some meaning in this trip. I had to.

“I went to see the Solomon Fresno retrospective the other day,” I said.

“Oh, what did you think?” Veidt said. “I thought they did a great job. My wife and I were crushed when he passed. He was my wife’s brother. He was much older than her, twelve years I believe.”

“I heard it was cancer,” I said.

“Heart failure,” Veidt said.

“Good to know,” I said, though my heart skipped a beat. “Did Fresno serve on Operation Argus?”

“I don’t know,” Veidt said. “If he did, we never discussed it.”

I doubted that, but I played along. “Well, some of his art seemed inspired by his service in the Pacific. The paintings of ocean life. The tropical birds, the peacocks…”

A brainwave seemed to pass through Veidt’s skull. “Huh,” he said. “Wasn’t Argus the guy who got turned into a peacock?”

“Yeah.” I was surprised he knew the myth, but even more surprised he was making the connection now. I kept going. “So I heard a story the other day. It’s pretty weird, but I’d want to get your take on it. This is just you and me talking, now.”

“Off the record.”

“Indeed. You know how the U.S. banned CFCs in the 1990s because of the Ozone hole?”

“Sounds familiar.”

“What if the Ozone hole was created by the Argus nuclear tests, and the CFC ban was used to cover it up?”

The admiral was impassive. He had the expression of granite.

I continued. “Solomon Fresno, who probably served on Operation Argus—he painted peacocks and spray cans. The motif of the eyes—it could represent all the holes punched into the atmosphere by the hydrogen bomb.”

“Sounds like you need to go back to grad school, son,” Veidt said, angered. “If we had done that, the world would have found out by now. You think we’re capable of hiding something as wild as that?” He folded his napkin on the table. “I think we’re done here. They already charged my card, so you’re set. Good luck with your podcast.” Before he stood up, he tapped the table. “Let it go. For your own good.”

I watched as he walked into the corner of the room, where an older woman in an elegant hat greeted him. She had to be his wife, Anna Fresno Veidt. They disappeared into the hotel.

Then I saw two dark-suited men replace the admiral in the doorway. They walked in my direction, and so I changed mine.

#

I wandered to the Del’s outside deck which faced the ocean. The bright, blinding San Diego fog was still lingering, mysterious, like the way this trip had unfolded.

I could see a plane taking off, lurching into the sky. Soon I’d be on one of those. I kept traveling to new places, describing them and animating them with ghosts. I’d been looking around with many eyes, each sight so glancing I never really saw anything.

I thought about the dark-suited men. Maybe I had seen too much.

I called Veronica. The phone rang several times, and I was relieved when it went to voicemail. I decided to leave a message. “Veronica, I’m sorry about the other day. I’m glad I got to see you, and you’re always welcome to visit me in Denver.” I could have left it there, but by some inner force I felt compelled to continue. “It hurts to me to say it, but it’s too bad nothing ever came of us. I’ve been thinking, and I’ve realized how difficult I’ve been—” I broke off. “I’ve been depressed. I need to change. What I mean to say is, I’m like—” Still I couldn’t say it. I hung up.

I turned around. The dark suits hadn’t followed me to the deck. Maybe I was in the clear; maybe I was paranoid. I waited.

A few minutes later, the phone rang.

“Mark,” Veronica said. “You left a message?”

For a moment, I couldn’t answer. The waves were lapping on the shore.

“You can delete it.”

“Uh huh,” she said, suspicious. She hung up.

When I had almost reached my car, the phone rang again. My hand was trembling as I answered. “So I heard your message,” she said, her tone neutral.

I was distracted. The dark-suited men were standing in front of my car. Both of them sported sour grins. With dread, I noticed the black glint of gunmetal at their hips.

Then Veronica said, with a note of optimism, “It seems we still have a lot to talk about. When are you coming back?”